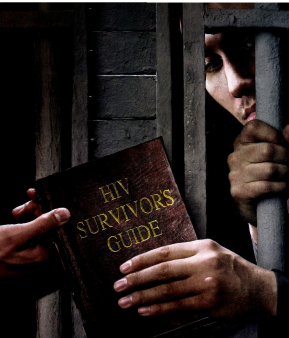

I’m not going to die in this place. HIVer Brian C., 41, recited that mantra during his three stints in the rough-and-tumble Philadelphia county jail system. His desperate prayer echoes among the nation’s positive inmates, who account for an estimated 12 to 18 percent of U.S. HIVers.

Granted, things aren’t as bad as they used to be. PWAs are no longer burned out of their cells, as they often were in the 1980s. Combination therapy has made AIDS-related death rates plummet. Even Alabama, the only state that still completely segregates positive inmates, opened up some programs to male HIVers in January. Nonetheless, for inmates nationwide, each day is a grinding struggle for halfway decent care. Prisoners with HIV are stigmatized, and confidentiality ignored. Rules and conditions vary widely among facilities, complicating treatment and peer support. Miserly HMOs and their frequently third-rate docs run the show, with little accountability. Few systems will fund the pricey treatment for hepatitis C, a leading killer of HIVers behind bars.

Yet survival is possible. POZ grilled prison advocates, inmates and ex-cons to get the inside scoop on how prisoners with HIV should handle the seven major challenges they face—and to remind HIVers on the outside of their comrades’ brutal treatment. Says HIVer Misty Rojo, 27, from a monitored pay phone at the massive Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF) in Chowchilla, where she’s locked down till 2009: “We’re just human beings trying to stay alive.”

CHALLENGE #1

DISCLOSURE DILEMMA

Telling people you’ve got HIV ought to be a choice, but on the inside it’s not that simple. Inmates often line up daily for pills, so “everyone knows what you’re taking—and a lot of rumors start,” says Gricel Paz, 39, a hep C–infected CCWF inmate and peer health educator. Former prisoner Waheedah Shabazz-El, 50, says that while doing time in Philly, she learned she was positive “in a room with no curtains. I was crying and everybody was walking by. I felt like killing myself.”

If word does get out, “people can be hurtful,” says John Bell, 57, an ex-inmate with HIV and hep C who now does prisoner-care outreach for the AIDS group Philadelphia FIGHT. “Guys will say to guys with HIV, ‘Stay away from me.’” That stigma deters many from testing and treatment.

What’s more, prison staff often flout patient-confidentiality laws, so an inmate’s status can race from a nurse to a corrections officer (CO) to the entire facility. Paulette Nicholas, 45, who did four years in Alabama’s Tutwiler Prison, says the warden “devastated” her children by casually telling them she had HIV during a Christmas visit (Nicholas hadn’t wanted to worry them). No wonder Shabazz-El, a Muslim, made sure to hide her HIV literature inside her Koran.

Inmates should:

>>Make sure disclosure is worth it. Misty Rojo points out that you need “a really strong character and coping skills” to reveal HIV in prison—so much so that short-timers often forego meds and conceal their status. For longer sentences, however, disclosing can reduce stress and isolation, and even win you respect. “I became a role model [after I disclosed],” recalls Kim Hunter, 42, who did nine years in New Jersey and is coinfected with HIV and hep C.

>>Pick friends wisely. Be extremely careful whom you tell about your serostatus—including people on the outside, since word can leak back in. Don’t be shy about reminding your confidants not to tell your HIV status to anyone else.

CHALLENGE #2

EDUCATING YOURSELF ABOUT HIV

You have to—because prisons seldom will. “The most [education] you might get is some video in orientation,” says Jack Beck of the Legal Aid Society of New York. Dennis Roman, 34, who spent 1996 through 2001 in and out of New York prisons, adds, “If you’re not educated about your meds, they’ll shove them down your throat.” On the other hand, Misty Rojo says, “If you know what you’re talking about, docs and nurses will more likely cooperate with you.”

First order of business:

>>Write for info. With no Internet and limited phone access, many inmates make a career of sending away for resources. Beck says knowledge warns medical staff, “‘This person is looking at what I’m doing.’” Start getting smart by contacting the groups listed in “The Hook-Up” —but remember, prison staffers often screen mail. Even correspondence that should be confidential (like letters from your lawyer) often isn’t.

>>“Invest in your karma” by reading or writing for inmates who can’t, suggests Jess West, incarcerated at the maximum-security Corcoran prison in California. Or teach someone to read—their lab reports, for example.

CHALLENGE #3

FIGHTING FOR TREATMENT AND CARE

In general, prisoners get HIV meds, but their actual HIV care often stinks. Inmates report endless waits for HIV or hep C testing—and sometimes they never see their results. Eddie Hatcher, 48, a North Carolina lifer without parole, says that he learned he was positive “by accident.” (Learn more about Hatcher’s controversial sentence at www.eddiehatcher.blogspot.com.) Paz at CCWF says, “The doctor will say to you, ‘Oh, you didn’t know you had hep C?’”

When transferring to another facility, prisoners may wait months for meds, be unable to get the same meds or even get “written up” for refusing meds due to intolerable side effects. Worst are incompetent or uncaring nurses or doctors, some of whom work only at prisons because they’ve lost their license to practice elsewhere (but not all pen docs are bad—see “Can HIV Care Click in the Clink?”). Ezra Davis III, 46, an inmate coinfected with HIV and hep C, says that his doctor at Corcoran once confessed that he knew nothing about treating HIV. Corcoran is by many accounts the worst pen for male HIVers in California; throughout the state, prisoners often see HIV specialists only over a TV.

Davis is also one of many inmates who claim prisoners have died in their cells because medical staff wouldn’t bring someone who’d “fallen out” (fainted) to an emergency room. Says Antoine Mahan, 36, of the California facilities where he’s done time, “No one ever went to the hospital until they were almost dead.”

How to get the best care you can:

>>Work the system. Get someone to explain your facility’s request-and-grievance process, then follow it precisely. “If you have several [health] items, choose one,” Philly FIGHT’s John Bell says, “and get that resolved” before tackling the next. If appealing a refusal, attach government treatment guidelines (see AIDSinfo, in “The Hook-Up”).

>>Stay polite, yet persistent. “I’ve asked [male] inmates to use the charm they once used with females,” Bell says. If necessary, take complaints up the chain of command, or get outside help (see Challenge #4, below).

>>Keep your own records. Prison officials often withhold records, misplace them, or won’t forward them to your next doc—but you should try to get them anyway. Also, record every detail in your own health journal. Make regular copies—by hand, if necessary—and mail them to an outsider. If you haven’t disclosed your HIV status, use code in case of a “shakedown,” or search (for example, “saw Dr. D. about my allergy”).

>>Know your correctional officers. The COs—prison police—often decide if you’re even allowed to visit the infirmary. Feel out who’s gonna support you and who’s not. A big no-no? Attitude.

CHALLENGE #4

SEEKING OUTSIDE HELP

Prison medical staff is often more likely to help you if they know others are watching. “If you have family, use them,” Bell says—for calling medical, involving outside agencies, or downloading information from the Internet. You can even have them call the warden’s office or, if no one responds, the Department of Corrections’ health division. (If they don’t respond, try state legislators or legal advocates.) Persistence pays—but anyone representing you should also remember to be courteous.

Try to cultivate ties with outside advocacy groups, too (see “The Hook-Up”). A professional pain-in-the-neck can work wonders. One advocate who withheld his name says that when he heard some inmates weren’t getting meds, “I called their medical director. Lo and behold, he fired one of the nurses and hand-delivered the meds.”

When working with outsiders:

>>Sign a release letting them discuss your case with medical staff (advocates can provide one if the prison won’t)—otherwise, says the Legal Aid Society’s Jack Beck, staff may invoke confidentiality laws to rebuff them.

>>Tell ’em the full story, including your treatment history, things staff has said or done that they shouldn’t have (or vice versa), exactly what you want from outsiders, whom they should contact and what they can’t or shouldn’t say or do—including spelling out your HIV status. Remember: All communications may be screened.

>>Tread carefully. Using outsiders may mark you as a troublemaker, so watch your tone. “Refrain from any talk that would [be seen as] a breach of security,” says Davis, who has repeatedly been transferred—so-called “diesel therapy” for rabble-rousers.

CHALLENGE #5

ORGANIZING AND PEER EDUCATION

Prisons don’t like it when inmates organize, period. Just try to start a group at his North Carolina facility, Eddie Hatcher says, and you’ll be “charged and placed in segregation.” But there are exceptions, like the pioneering AIDS Counseling and Education (ACE) program at the Bedford Hills, New York, women’s prison, or Corcoran’s Chronic Infectious Disease committee.

If you are allowed to start an official group, expect initial wariness from inmates (maybe keep “HIV” out of the name)—and heavy staff intervention. In late 2003, inmates at CCWF started PRIDE—“the first support group run by inmates in five years,” says cofounder and HIVer Beverly Henry, 51. However, adds fellow cofounder Misty Rojo, “We didn’t want a CO sitting there listening to our medical information, so they shut us down after three weeks.”

Aspiring organizers should:

>>Appeal to an outside AIDS organization. “It’s much easier to get a group off the ground” that way, says Jack Beck of Philly FIGHT. But look for inside sponsorship, too—perhaps from a counselor or social worker.

>>Make a strong case. “Show [staff] there is a need,” Beck says—for example, the lack of info on HIV and hep C prevention. Ex-con Dennis Roman says that after he and others devised an AIDS curriculum at New York’s Mid-State, “it took three months to get a response, but they were all for it.”

You can go the underground route, too. Shabazz-El says that when she worked in the prison’s gym, “HIV girls came—we knew each other from clinic. We’d talk about the meds, the side effects, the people in denial.” Former inmate Hunter started an afternoon walking group in the yard: “It got bigger and bigger, though other inmates didn’t know we were talking about HIV.”

Official or not, peer educators should:

>>Be a stand-up friend. “You have to be people’s ears and not break confidentiality,” writes Chowchilla’s Paz, who helps inmates read their labs or write appeals. “I feel glad and proud when they come back and say, ‘I won—now I’m going to have the test or treatment I need.’”

>>Seize the power of print. Sometimes you can kickstart a peer network just by laying out a newsletter and striking up a conversation.

CHALLENGE #6

PRESERVING BODY, MIND AND SOUL

The joint is stressful. The food is awful, and “special diets” for people with HIV or hep C are rare. Drugs are smuggled in far more often than clean needles to shoot them with. Sex happens plenty, though condoms or dental dams are not usually allowed or provided. How can you possibly take care of yourself?

>>Eat as well as you can. Snag—or befriend someone with—a kitchen job. That means access to rarities like fruits and vegetables. You can also buy special foods at the canteen and perhaps get vitamins via mail order (at “exorbitant” prices, notes Corcoran’s Davis) or care packages via family. “Figure out the least-bad options,” says Cynthia Chandler, whose Oakland, California, group Justice Now advocates for women prisoners with HIV. She means low-fat, high-protein foods like rice and beans, dried fruit and nuts, seafood, chicken, instant oatmeal and ramen noodles (skip the sodium-packed flavor packets). Have family or friends get a canteen list to an outside doctor or nutritionist, who can circle the healthiest options.

>>Hop the recovery wagon. If you’re addicted to drugs, work with your lawyer to land in a recovery wing or track, and try to get yourself to every program, workshop or AA (Alcoholics Anonymous) or NA (Narcotics Anonymous) meeting you can. The parole board will take note, and this will also help keep you away from drug-related violence. Clean after years addicted to heroin, Gricel Paz says, “If I can do it, anyone can!”

If you must use drugs, don’t shoot them. You should smoke or snort, but don’t share straws. If you must shoot, don’t share your syringes, and clean them thoroughly in full-strength bleach. (Contact the Harm Reduction Coalition at 22 W. 27th St., New York, NY, 10001; 212.213.6376; or www.harmreduction.org. They can give you info on safe tattooing, too.)

>>Have safe sex. Prison punishes those caught having sex, but many have it anyway—from brutal rape (not quite as widespread as HBO’s Oz suggests) to what Corcoran inmate Robb Rogers, 47, calls favors “bought and sold as a means of survival,” to long-term relationships. If you can’t get latex and water-based lube (Vaseline destroys latex), consider oral sex, mutual masturbation (both pose little HIV risk) or solo action. Says Rogers, “Can’t nobody play with me better than me!” Some inmates even improvise condoms or dental dams with latex gloves, trash bags or Saran Wrap. (Yep, it’s that bad).

>>Stay sane. “You must,” says Chowchilla’s Paz, “or this place will break you down.” Try prayer, meditation, exercise, helping others or whatever brings you solace. “I go to church, read a lot, play Scrabble or cards with my friend, and say hi to many but [only] know a few,” says Delores “Dee” Garcia, 54, an inmate at California’s Valley State prison who’s evaded HIV but has hep C. Corcoran’s Davis keeps it together by “writing letters and fighting battles for those who have a hard time fighting for themselves.”

CHALLENEGE #7

PAROLE AND LIFE OUTSIDE

Too few facilities prepare inmates with HIV or hep C for this treacherous transition. Suddenly, there’s “no one to tell you when to get up, go to bed, eat, take a shower,” says James Rolkiewicz, 40, who, after more than a decade in a New Jersey pen, is learning to handle his HIV and hep C on the outside. Where do you find work, housing, health care? How do you mend broken family ties? Handle sex with an infectious disease? And stay off drugs? Sadly, programs for HIVer parolees like Philadelphia FIGHT’s Project TEACH Outside (see “With Conviction” ) are few and far between.

Outgoing inmates should:

>>Network like a mutha. “At least six months prior to parole,” Davis says, contact as many outside agencies as possible, so you can register the minute you’re out. “Investigate your options in housing, halfway houses [to support sobriety], 12-step meetings, employment, clothing, food stamps, transportation and churches,” urges ex-inmate Paulette Nicholas, now a case manager for homeless people with HIV. “Write letters, explain your situation, and get their office hours, location and a contact person. Plan ahead to receive your Social Security card and driver’s record while still inside, so you can get your license or state ID when you leave.”

>>Pack your pills—and all your medical records. Again, work with outside agencies to line up your outside doctor and first appointment well in advance. (Bring notes and files!)

>>Seek positive support. Investigate ex-prisoner groups like New York’s Fortune Society (53 W. 23rd St., New York, NY 10010), HIVer support networks at your local AIDS agency, or meetings of AA (Grand Central Station, P.O. Box 459; New York, NY 10163) or NA (P.O. Box 9999; Van Nuys, CA 91409).

>>Find a purpose. Focus on job, family,spirituality —whatever keeps you out of the pen and living healthy. Many HIVer ex-inmates do HIV peer education or work to make prisons safer. Gricel Paz says that even though she’ll be nearing 50 after a 2013 parole, “I’m ready to start living life the right way. I can’t wait to tell the world who I was and how people can change.”

_________________________________________________________________

“C” No Evil

Prison officials try to ignore the raging hep C epidemic—but Phyllis Beck won’t let them

Deceased. That’s what Phyllis Beck became used to seeing on returned copies of her Hepatitis C Awareness News. Beck, a former injection drug user with hep C, runs the Eugene, Oregon–based HCV Prison Support Project. Before Awareness News was unexpectedly defunded in February, Beck sent it to thousands of inmates with the liver-ravaging hep C virus (HCV), which inhabits an estimated 20 to 40 percent of the nation’s prisoners, putting about 6 percent at risk of early death. (Beck hopes to get new funding for Awareness News soon.)

Most prisons find ways to withhold costly interferon/ribavirin HCV treatment, but in 2000, Steven Meljado—since released—became the first prisoner in Oregon to get the drug after Beck lobbied the legislature. “Prison docs told me I was ‘too far gone’ for treatment,” says Meljado, 48. Surprise! They were wrong: Meljado cleared the virus.

Tips for tackling hep C behind bars:

Ask to be tested—especially if you shoot drugs or have a homemade tattoo.

Don’t panic! Only 15 to 20 percent of people with hep C develop serious liver disease. Get blood tests of your HCV viral loadand genotype (type 1 is often harder to clear than 2 or 3).

Love your liver If you have hep C, drinking, drugging and a high-fat, high-salt diet will stress it. Chug plenty of water.

Get educated Beck’s your best bet. Write HCV Prison Support Project, P.O. Box 41803 Eugene, OR 97404. HCV has a hotline—866.HEPINFO—and check out www.hcvinprison.org.

_________________________________________________________________

Outside In

Hey, HIVers on the outside: Think there’s no way to help inmates with HIV or hep C? Think again

Be a pen pal. Ask local AIDS groups if you can help answer inmate mail (they’re often overwhelmed by it). Or simply get your address to an inmate via the advocate groups in “The Hook-Up”.

Help ’em stay sober. If you’re in AA or NA, you can “bring meetings” to inmates—talk to your group’s “H&I” (hospitals and institutions) chair or to your group chair about starting H&I visits. Faith-based organizations often volunteer in prison, too.

Get in the loop of veteran advocates and groups (see “The Hook-Up”). “We would be excited to figure out how to pass our program to other parts of the country,” says Laura McTighe of Philly FIGHT’s Project TEACH Outside. Says Delores “Dee” Garcia, from inside California’s Valley State prison, “Get out of those recliners and help us live—please!”

_________________________________________________________________

Myth vs. Reality in the Pen

1. Myth: Prison is an HIV breeding ground.

Reality: Most inmates with HIV got it before incarceration.

2. Myth: Health care is better in prison than outside.

Reality: Only if you’ve had no health care at all outside.

3. Myth: Men’s prisons are tougher on gays.

Reality: It’s tougher on the weak or effeminate of any sort—and gay men in prison are often quite tough themselves.

4. Myth: Women’s prisons teem with lesbians.

Reality: Many women prisoners are coming off abusive relationships with men and find intimacy among one another— but they don’t all identify as “lesbian.”

5. Myth: Prison rape is common.

Reality: Brutal rape sometimes occurs in male prisons—but coercive sex is more often an adaptive or survival move. Most rape in women’s prison is committed by male guards.

_________________________________________________________________

The Hook-Up

Where inmates — and outside activists — can get the 411

AIDSinfo

P.O. Box 6303; Rockville, MD 20849-6303

800.HIV.0440; www.aidsinfo.nih.gov

This government service takes questions and provides federal guidelines to treatment for HIV. For easy-to-read guideline summaries, contact: The New Mexico AIDS Info Net (P.O. Box 810, Arroyo Seco, NM, 87514; www.aidsinfonet.org)

American Civil Liberties Union

ACLU National Prison Project

Attn: Ms. Jackie Walker

733 15th St., N.W., Suite 620; Washington, DC 20005

202.393.4930 (collect calls from inmates accepted); www.aclu.org

Write to Walker for referrals to AIDS or legal services near your facility, or answers to questions you don’t know where to take.

Body Positive

19 Fulton St., Ste. 308B; New York, NY 10038

212.566.7333 (no collect calls); www.bodypos.org

Publishes the acclaimed magazines Body Positive and the Spanish-language SIDAahora (send a check for whatever you can; no requests turned away for lack of funds).

California Prison Focus

2940 16th St., Ste. 5B; San Francisco, CA 94103

415.252.9211 (no collect calls); www.prisons.org

Inmates nationwide can get one free issue of Prison Focus, a quarterly packed with prison news (subscriptions $5, sliding scale; stamps accepted). CPF also gives referrals to other resources.

National Minority AIDS Council

NMAC Prison Initiative

1931 13th St. N.W.; Washington, DC 20009

202.483.6622 (no collect calls); www.nmac.org

NMAC will refer anyone to prisoner or ex-offender services in their area, or help community groups better serve these HIVers. They also publish several brochures on HIV and hep C in prison.

Philadelphia FIGHT

1233 Locust St., 5th Floor; Philadelphia, PA 19107

Attn: Laura McTighe

215.985.4448 (no collect calls)

FIGHT will send its excellent Prison Health News or other material from its AIDS Library free of charge to prisoners anywhere. Philly-area parolees should inquire about Project TEACH Outside (see “With Conviction”).

Positive-Prisoner Listserv

E-mail maddow@rcn.com to join activist Rachel Maddow’s positive-prisoner list serv, or hook into the prison committee of AIDS Treatment Activist Coalition (www.atac-usa.org) by e-mailing Julie Davids at jdavids@champnetwork.org, or calling 212.966.0466 ext. 1226.

POZ

Write to: POZ Subscriptions; Old Chelsea Station; PO Box 1937; New York, NY 10114-1937. Our monthly guide to everything HIV is free to any positive prisoner.

Project Inform

Outreach and Education Department

205 13th St., Ste. 2001; San Francisco, CA 94103-2461

Inmates: Call 415.558.9051. Treatment Hotline: 800.822.7422

www.projectinform.org

Acclaimed treatment hotline plus great “HIV 101” information sheets and newsletters (including WISE Words, just for women), all free to prisoners.

Women ALIVE

Attn: Precious Jackson

1566 South Burnside Ave.; Los Angeles, CA 90019

323.965.1564; toll-free hotline: 800.554.4876 (Spanish and English); www.women-alive.org

Write this women’s HIV group for free woman-focused HIV treatment information plus their biannual newsletter.

Comments

Comments