|

| Recent reports from the amfAR public policy office |

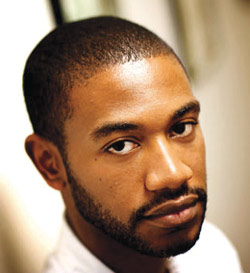

Greg Millett, MPH, is a vice president of amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research, and the director of its public policy office. Kali Lindsey is deputy director. The dynamic duo leads the efforts of amfAR to educate policymakers, the media and the general public on policies that will help end HIV/AIDS as a public health concern.

Prior to amfAR, Millett was the Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (HHS/CDC) liaison to the White House Office of National AIDS Policy (ONAP). Before that he was a senior policy advisor at ONAP. He was one of three principal writers of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy. His research on HIV disparities among black men who have sex with men (MSM) has been credited with changing the assumptions of researchers.

Before joining amfAR, Lindsey was director of legislative and public affairs for the National Minority AIDS Council (NMAC). Prior to that, he was senior director for federal policy at Harlem United. He also was vice president for federal government affairs at the now-defunct National Association of People With AIDS (NAPWA).

As HIV-positive African Americans, both men use their personal experience living with the virus to inform their public policy work. They also use their complementary skills, Millett the epidemiologist and Lindsey the grassroots activist, to further their efforts. Here, they share domestic and global priorities for 2016.

Let’s start with your domestic priorities for this year.

Millett: Advocates did an amazing job in 2008 in getting presidential candidates John McCain and Barack Obama to agree to a National HIV/AIDS Strategy. We would like to join other advocates in doing similarly in the 2016 elections.

On the Democratic side, we’ve met with the Hillary Clinton campaign and plan on meeting with the Bernie Sanders campaign. We’re waiting for the Republican field to whittle down before we can figure out which campaigns we need to reach.

It’s important that the next administration continues the successes that have been made at the federal level, continues to fill the gaps that we have in implementing the strategy, and works hard to implement the strategy at the local level.

Lindsey: One of the things amfAR has always prioritized and continues to prioritize is the need to focus on key populations in our response to the HIV epidemic, both domestically and abroad.

As we have those conversations with a prospective president for 2017, we want to focus on populations who have remained historically underserved, but are overrepresented in the HIV epidemic, such as young gay men of color and African-American women.

We also want to focus on the need to expand Medicaid in the South, and ensure that promising HIV research, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and treatment as prevention (TasP), can be realized throughout the South and in key populations.

We’ll be holding a conference this spring on Capitol Hill highlighting these issues for members of Congress and their staff. We’re going to emphasize the importance of funding HIV research by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), especially investments in cure research.

|

| Greg Millett |

Millett: Another focus for us that we did not anticipate was making sure that we hold ground in our successes when it comes to injection drug users (IDUs).

The IDU epidemic has been a success story for so long in the United States, with a 70 percent decline in new HIV diagnoses among IDUs between 2002 and 2011, and that continued through 2013, according to CDC data.

But the Scott County HIV outbreak among IDUs in Indiana was a canary in the coal mine for a lot of us: that we can’t rest on our laurels, that there still is a possibility that we could see a spike in cases among IDUs. The thing that was particularly worrisome about that incident was the striking number of cases, over 160.

We are committed to rolling out a multifunctional online map of syringe exchange programs. People can search what’s taking place in specific localities, how many people are being served, how long that program has been up, and what type of funding it’s receiving. People would be able to compare that information to the epidemic among IDUs within those states.

If there’s a silver lining to the HIV outbreak in Indiana, it’s that policymakers who were against syringe exchange programs are listening.

|

| Kali Lindsey |

Lindsey: Syringe exchanges are a big success story, but unfortunately many IDUs diagnosed with HIV experience worse health outcomes after their diagnosis. Localities need to figure out how they can bring their systems and resources to bear to address that.

The opiate epidemic, largely in white communities, often not urban, is shaking those communities to their core. It’s causing them to call their governors, and their governors are calling their members of Congress.

Let’s talk about your global priorities.

Lindsey: The language du jour in the global response, I’d say, is fast-tracking scale-up. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) came up with its fast-track strategy with its 90-90-90 goals. [That means having 90 percent of people living with HIV know their serostatus by 2020, getting 90 percent of those people on treatment, and having 90 percent of that group achieving an undetectable viral load.]

Largely, the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria have embraced those goals. Capitol Hill still hasn’t, so there’s a lot more work that we need to do to restore losses to PEPFAR.

We have a critical opportunity to deal a heavy blow to the HIV epidemic if we concentrate our resources and our efforts, but we need the level of investment that is necessary to marshal that response, and we’re going to be having that conversation concretely throughout this year on Capitol Hill.

Millett: Another priority for us in terms of global HIV is access to generic medications. The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is probably not going to be passed until the lame duck session in late 2016, which gives us an opportunity to talk with members of Congress about some TPP provisions that we think unfairly limit access to generic medications for countries that are part of the pact. It has implications not just for HIV, but for hepatitis C and other conditions.

Lindsey: Returning to PEPFAR, we want to acknowledge its enhanced efforts to engage a broad cross-section of civil society to get the best results from its country operational plans (COPs). [COPs are like our National HIV/AIDS Strategy.]

Millett: One way we’re helping out with the COPs process is amfAR developed a database last year, called the PEPFAR Country/Regional Operational Plans database, which is available at copsdata.amfar.org.

COPs aren’t friendly documents; they’re about 500 pages, usually a PDF or a Word document, and that’s only for one year, so imagine several years of these documents, trying to understand where the trends are in funding, what’s taking place for key populations.

So we pulled these data into a database where you can do trend analyses, see how funding has increased or decreased in particular countries. What were some of the specific contracts? Who was awarded those contracts and what were they awarded to do? All of that is laid out very nicely graphically.

We’re working with civil societies in different countries to help them become used to using the database, so that they can take a look at what’s taking place within their own countries, and to help it inform planning efforts as they move forward with the PEPFAR process.

Why do you work in public policy?

Millett: I’ve seen the power of policy to impact people’s lives. To reduce HIV cases or to keep people in care, policy is where the levers of powers are.

Lindsey: Death from HIV/AIDS wasn’t my experience, neither in my childhood nor once I was diagnosed, but rampant discrimination was. That drives me.

1 Comment

1 Comment