Life with HIV is a cabaret! As least it is for singer-dancer–turned-psychoanalyst Bradley Jones, PsyD, LCSW. The long-term survivor spent nearly 10 years on Broadway in A Chorus Line before leaving the Great White Way, going back to school and launching a Manhattan-based therapy practice. But that doesn’t mean he gave up his love of the spotlight. He recounts his story—tumultuous childhood, offstage debauchery and current career path—in his musical memoir, Dr. Bradley’s Fabulous Functional Narcissism: The Psychoanalytic Odyssey of a Once Glorified Chorus Boy, which has run in New York, Connecticut and Los Angeles. An April 30 performance at the Laurie Beechman Theatre in Manhattan will benefit Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS. (You can get tickets here.) We emailed with Jones shortly after a recent performance to learn more about his insights on HIV and functional narcissism.

Before we get into your personal story, let’s talk about your therapy practice, especially since you’ve worked in HIV-related issues for decades. What are the biggest concerns facing people with HIV today?

Today, I find—and I am not saying something new—that most people struggle with HIV stigma. Patients feel disrespected by being asked by prospective sexual partners if they are “clean,” and they often cannot make sense of the dissociated and random quality of people’s choices around who they fuck and who they date. It’s understandable that a patient I’m seeing might feel frustrated when he meets someone he’s attracted to who will go into a sex club or back room and fuck indiscriminately but will not date my patient because he is HIV positive. An accumulation of this kind of disappointment becomes injurious, and people eventually want to throw in the towel.

We all struggle with our ability to accept the inconsistencies of people—I believe that transcends the issue of HIV. At times, people are nothing if not tremendously disappointing. Loneliness, I believe, may be at the heart of all of this. It remains one of the biggest issues single people with HIV have to come to grips with. And because I have a partner of 32 years, I cannot always know exactly what my single HIV-positive patients might be feeling. I ask them to educate me. Over time, I have gotten a sense of how excruciating the loneliness can be, and it is not such a reach to understand how it can lead to extreme behaviors. For example, I have come to understand why crystal meth use is “functional.” “Tina” and other drugs or intense state-changing behaviors can help to counter anxiety, depression and terrible feelings of extreme isolation that some people with HIV experience. Drug use works—until it doesn’t.

In your observations, how have the concerns of the HIV population changed over the decades?

When I began my practice in the mid-’90s, protease inhibitors had just been introduced, and the medical community was finally doing a better job with staving off death. People were not dying as frequently, but it still felt like the scythe of our mortality was everywhere. Men believed they would perish, and they needed a place to have their intense fears listened to and metabolized. Others had spent their financial fortunes thinking they would soon be dead, only to find themselves living with nothing in their bank accounts left to sustain them. The grief and mourning of this unfathomable loss were also often very present in my consulting room. My long-term survivor patients still need to revisit the indelible devastation stamped in their mind’s eye by the late ’80s and ’90s. The goal of therapy is not about trying to rid patients of these unbearable images. It’s about helping them to develop a narrative about it that shifts and changes over time. As it transforms, it becomes more bearable.

I have found that people who have trauma in their histories process things differently. If a patient has been severely emotionally neglected or abused in their early development, they might have had a harder time integrating their feelings about being positive. To these people, HIV infection becomes another felt abuse, and it can activate powerful feelings not only about infection but also about the denied or disavowed abuse they have experienced in their youth. In some cases, we are surprised to find these individuals have more work to do than integrate feelings about HIV infection. Sometimes, we find HIV infection can be the catalyst to deeper and more painful work.

I raise this distinction because there are some therapies that appear to confront and chide patients for extreme emotional reactions to seroconversion without taking time to explore the various determinants that may be at play. I remember, back in the ’80s and ’90s, we had a support group here in town called Friends in Deed. The “support” group facilitators at FID would not let anybody in our group “go victim.” So much so that it felt as if we were being trained to reinforce patterns of denial and dissociation, where any painful feeling we had about our HIV status would go underground for fear of being called out in front of our peers. So we all pretended having HIV made us stronger, and we learned to stay “positive.” I saw the usefulness of these interventions. It was an extremely emotional time, and we needed ways to cope. Another part of me thought it horrifying because it had potential to publicly shame, especially the more emotionally fragile people in the support group. In my psychotherapy practice, I try to make room for all of it—even “the victim” gets his say. I attempt to explore all of the intense emotions available to us, and I will search for deeper meaning in both the present and the past. We listen and respond to “the victim” but don’t let him be the dominant voice.

Bradley Jones in his memoir musical “Dr. Bradley’s Fabulous Functional Narcissism: The Psychoanalytic Odyssey of a Once Glorified Chorus Boy”Courtesy of John Seemann

I don’t know if this is superficial or politically incorrect to say, but when I caught your show, I couldn’t help but noticed that you look fit and fantastic.

What? Why would that be superficial or politically incorrect? I love that you were checking me out! A great compliment at my age! Thank you!

Can you update us about your health, especially in relation to HIV? For example, you had mentioned a knee issue—was that HIV-related?

No, the knee injury that eventually took me out of A Chorus Line I sustained in the early ’80s. At that time, I do not believe I had been infected yet.

I did seroconvert in the late ’80s, and I have been lucky enough to be on the cusp of each new class of antiretrovirals. I believe this is the foundation of what has kept me alive. At various times, I have been on what I call “the downside of the mountain.” Early on, I remember feeling dreadful when I was taking the drug AZT [the first HIV med]. At other times, when various medication “cocktails” stopped working, I began to develop thrush, I looked very thin and I had somewhat pronounced lipodystrophy in my face. About six years ago, I also developed HIV-related arteriosclerosis, and I had a heart attack. Three stents later, I’m good as new—extremely lucky—and very thoughtful about my intake of cholesterol. I also have had lots of basal cell cancers. The treatments for this are not much to be bothered about, but certainly a nuisance.

And ever since I was 13 years old, when I became interested in acrobatics and dancing, I lost all my chubby weight and developed a relatively stable “body self.” Exercise is a huge part of the way I cope. I have a small amount of body dysmorphia—I still see myself as a chubby kid. I don’t mind that too much. It keeps me at the gym, and perhaps this is one of the positive aspects of “healthy narcissism.”

Did HIV play a role in your decision to pivot from Broadway to therapy?

I showed no signs of infection until I was well ensconced in my undergraduate process at age 32, and, again, I don’t believe HIV impacted my decision to make the transition out of show business. But when I did learn I was infected, I was very happy to be in school, as I had a wealth of support around me to come to terms with my feelings about the diagnosis. At that time, infection was a death sentence. I didn’t feel sick, but I remember scrambling around for some way to make sense of the fact I would most certainly be dead much faster than I ever could have imagined. I remember being given a book by one of my psychology professors, Existential Psychotherapy by Dr. Irvin Yalom. In it was a story about a child who watched a dead leaf fall from a tree. Without thinking, the child picked up the leaf and tried to put it back on the branch from which it came. When the child failed to reattach the leaf to the tree, he began to cry. That moment became the catalyst for that child’s process of comprehending death and finitude. At the time I read that story, I had never fully pondered the fact that I would eventually die. It was my late education about the existential condition. So with the convergence of HIV infection, Yalom’s book, psychotherapy and writing many papers about HIV, I began the process of integrating my feelings about infection. Oh yes, I lived. That also helped. Today, it’s more a matter of negotiating a thought or two about how I have lived, and so many have died before me. I’m not sure I struggle with survivor’s guilt, because I don’t feel as if I have done anything wrong by living. But I still find the randomness and complexity of it so unwieldy. It still quite often feels real and unreal to me, all at the same time.

Psychoanalyst Bradley JonesCourtesy of Drew Geraci

The title of your show is Dr. Bradley’s Fabulous Functional Narcissism. For us non-therapists, what the heck is functional narcissism?

Psychoanalysis is by nature very “scholarly,” and it often gets a bad reputation for being inaccessible. If one can get past all the snootiness, then contemporary psychoanalytic thought is jam-packed with great ideas about how to understand human nature, especially the issue of narcissism. The term “functional narcissism,” coined in the 1980s, refers to the behavior a narcissistic person exhibits. People with NPD (narcissistic personality disorder) are on a continuum of narcissistic vulnerability (many of us to some degree) and tend to be haughty, grandiose, easily injured, and they lack the ability to have empathy for other people’s struggles. Narcissistic people have trouble recognizing that other people have perspectives different from theirs, and they don’t respond well to criticism. They’re often know-it-alls and in some cases can be manipulative. Narcissistic people struggle tremendously with interpersonal relationships.

Early Freudian concepts of narcissism revolved around the idea that due to early emotional deprivations and trauma, children get narcissistically “fixated” and develop too much self-love. When a child develops too much self-love, there is no more energic “libido” remaining to “cathect” (develop feelings for) others. GACK! Confused? Yes, me too. That is why I much prefer more contemporary theories that argue that narcissism emerges when a young child’s emotional life is not acknowledged, accepted and responded to appropriately by their caregivers. When this kind of “mirroring” is absent, the child begins to feel empty inside. And as this emptiness grows, he has to do something to try to make himself feel better. So he begins to develop an unconscious fantasy of becoming perfect—he reaches for a “self-ideal” he hopes will give him a sense of emotional stability. It’s in the service of this quest for a self-ideal that the egotistical and self-absorbed behavior begins to emerge. This behavior has been described by therapists as “functional,” as it symbolizes the unhappy child’s desperate attempt to repair the empty feelings he lives with. It is important to say that children do not choose a path of narcissism. It’s what analysts refer to as an “emergent adaptation”—an unconscious means of survival due to the feelings of emotional deprivation he lives with. Unfortunately, this attempt at reaching for perfection can’t be attained, so the child is left in a continual state of emotional hunger, has a voracious need for persistent validation and is prone to what analysts refer to as emotional fragmentation. Alas, what is functional about narcissism does not ultimately quell the emotional pain—it is only an ersatz attempt.

What role did functional narcissism play in your life? And does it have any connection to your contracting HIV?

I grew up in a violent alcoholic family system. My parents struggled with being terminally unique. They did it with flair! They were lovable—“fabulous” as mother would put it—and always wanted the best for me. But their affinity for a lavish lifestyle and love for “the party” took precedence—they were inebriated children having children. They were unable to meet their own emotional needs, so how could they meet mine? At a very tender age, I remember myself reaching for perfection to overcompensate for the emotional lack I felt. For example, at age 12 or 13, I found myself exaggerating and telling tall tales that aggrandized my daily life. I was completely unaware that behind these early pretentions, I was harboring longings and unmet emotional needs my parents were incapable of responding to. I could never have allowed those vulnerabilities into consciousness because it would have caused too much shame. I became emotionally cut off from myself (dissociated), impenetrable and, not unlike my mother, had to control everything.

In some ways, my reach for perfection served me. I left home at 18 years of age and in short order became a successful Broadway dancer. But I quickly became disillusioned when I found that working on Broadway did not fill up the emotional hole inside. In my endless adult search for something to quell the emptiness, I developed a serious cocaine addiction. Cocaine was an expansive drug for me—the perfect way to counter the depression I lived with. And that is where I believe my narcissism converged with HIV infection. During the early 80’s, the beginning of the AIDS pandemic, I was, not surprisingly, very sexually active. By day I was in dancing class, going to the gym and volunteering as a “buddy” for GMHC [the Buddy Program connects HIV-positive clients with volunteers who provide social support]. By night, I was this manic cocaine addict who was having unprotected sex in those very creative back room bars of the day. It was the deadly combination of intense emotional need (which I was unaware of) and grandiosity that didn’t allow me to adequately assess the danger around me. The rules around safer sex did not apply to me. I actually came to believe I was exempt from becoming infected. HIV became a “not me!” experience, and I repeatedly put myself in harm’s way. Simply stated, I believe my narcissism in many ways potentiated my chances for infection.

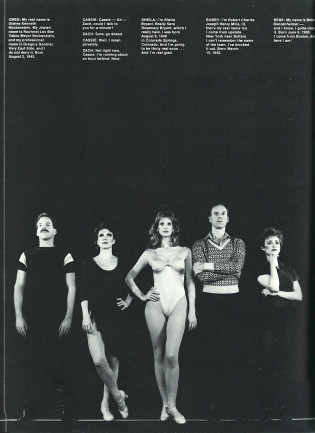

From left: Bradley Jones, Donna McKechnie, Cynthia Flemming, Ron Kurowski, and Tracey Shayne in the 1986 Broadway company of “A Chorus Line”Courtesy of Martha Swope

In your current cabaret show, backed up by an amazing quartet called The Freudians, you sing a selections of tunes that wonderfully capture the themes you’re talking about, such as “Life Is Absolute Perfection” from Candide. You obviously know your way around the American songbook. What Broadway show best represents your life?

I see parts of my life in many shows, so I am not sure I can pin this down to one. But when shows brilliantly capture unmet longings in music and story, I am apt to strongly identify. I am sure this is why I stayed in A Chorus Line for almost a decade. I love lyricists: Lorenz Hart, Oscar Hammerstein, Adam Guettel, and the most magnificent is Sondheim. Sondheim also writes brilliantly about ambivalence. When I see ambivalence masterfully depicted on the stage, I often imagine it is written just for me. Company, Follies and A Little Night Music have brilliant images of people who struggle with their ambivalence. Those are the shows that send me over the moon.

Similarly, what Broadway character do you relate to most?

I was introduced to Broadway shows in the 1960s. I relate to little Oliver [from Oliver!] because he was a victim who was saved and found love. I relate to Dolly [from Hello, Dolly!] because she gets to wear a fabulous red dress, dances with gorgeous male waiters and gets to start her life over. More recent characters might be Fosca from Passion. Fosca is a character who loves obsessively and makes no apology for it. I also relate to George from Sunday in the Park with George because he is driven—he had to make a hat where there never was a hat. I also have a bit of Tessie Tura from Gypsy in me as well. She is the whore with the heart of gold. Yes sir, I sure can relate to Tessie.

What general advice would you like to impart with the HIV community?

I demur at giving advice because things are too complicated to be reduced to “advice.” Where I do believe I might be helpful to your readers is in choosing a therapist. My thought is to stay away from people who call themselves experts. If someone is touted as an expert by others, that is one thing—that person has perhaps earned that moniker. If a therapist calls themselves an expert, it is more than likely an issue of self-promotion. There are plenty of narcissistic people in the helping professions. Run for the fucking hills. I also recommend auditioning at least three therapists before you settle on someone. A person seeking treatment needs to make sure a prospective clinician is well trained and has had hundreds of hours of clinical supervision. To my way of thinking, a successful treatment is a matter of finding the right fit. For example, if you are a patient who needs a lot of relatedness, a classical analyst who privileges anonymity will drive you mad. It will drive you even more mad if that therapist blames you for the feelings you might have about their tendency to withhold. If you are a person who needs to expand in the consulting room, an expansive therapist is not a great match. It will be a fight for the spotlight. Good therapy is a mutual endeavor. It is also bidirectional and must include the therapist’s willingness to consider what biases and blind spots he or she is bringing into the room. As it is said: “The observer is being observed.” Take time to find the right therapist, and make sure you feel you can share anything with that individual. Most importantly, a prospective patient needs to feel free to share what it is about the therapist he or she does not like. That’s often when the work can go into extremely illuminating places.

Finally, is there any parting message you’d like to leave our readers with?

I’m just so pleased we’ve come so far! From where I stand, I’m thrilled with the advances made by science that help keep having HIV manageable. The fact that I take one pill a day, rather than the fistful I took morning and night back in the day, feels like a miracle. There is every indication that newly infected men and women who will remain “undetectable” from the beginning may lead less harrowing lives than those of us who were on the frightening ride up and down the mountain during the late ’80s and early ’90s. Awful medication interactions and changes, lipodystrophy, skin cancer and the chronic inflammation that prematurely ages our bodies may be becoming things of the past. But even with this good news, the question remains: How do we gaze into the future at the edge of uncertainty with curiosity rather than dread? That is one of the complicated questions most people are trying to solve when they come to therapy, and it is not relevant only to those of us who live with the virus. The answers may prove to be fascinating but also quite complex. I suspect it will take time, patience and a tremendous amount of empathy to sort it out. As stated previously, there are no easy fixes. As philosopher Jacques Derrida asserted: “If life were simple, word would have gotten around.”

For tickets to Jones’s April 30 benefit performance in Manhattan, click here. For more about his therapy practice, visit DrDBradleyJones.com. And to learn more about Broadway Cares/Equity Fights AIDS, read the POZ cover story “The Show Must Go On.”

3 Comments

3 Comments