The verdict is in. The one-two punch of President Donald Trump’s proposed federal budget and the House Republican health care bill, if actually enacted, would deal a devastating blow to people living with and at risk for HIV. And while the U.S. epidemic, which has been steadily improving on many fronts in recent years, would take a major hit, the president’s proposed cuts to global HIV funding could prove cataclysmic to developing nations.

An all-male gang of 13 Republicans in the Senate is now faced with the daunting task of adapting the American Health Care Act (AHCA) to appease 50 members of the Republicans’ slim 53-seat majority. In a recent joint letter to senators, 133 HIV organizations stressed that the bill that passed the House without a single Democratic vote on May 4 “would return America to a time when health care coverage was out of reach for too many people with HIV.”

The letter lavishes scorn on the bill (which the Senate will apparently jettison in favor of starting from scratch) for its billions of dollars of cuts to traditional Medicaid programs; phasing out of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA, or Obamacare) expanded Medicaid programs; erosion of key protections against health-plan-related discrimination that benefit people with HIV; and problematic changes to the formula for determining subsidies for the premiums of private health plans obtained on the open, or “nongroup,” market.

Addressing the president’s proposed 2018 fiscal year budget, the grandly titled “A New Foundation For American Greatness,” Dana Van Gorder, executive director of Project Inform, says, “Donald Trump has shown complete and utter contempt for people with and at risk for HIV. This proposal is so offensive that even conservative Republicans find it frightening, and it has only a modest chance of passing in its entirety. Still, as a reflection of the values of this administration, it is morally bankrupt and uncivilized.”

“President Trump’s heartless budget proposal explodes hard-fought and effective bipartisan public health policy in fighting HIV/AIDS,” says Senate Minority Leader Charles E. Schumer, a Democrat from New York. “This budget’s cruelty and counterproductiveness is unparalleled, and Democrats will seek allies and fight tooth and nail to make sure this proposal doesn’t see the light of day in the Senate.”

Senate Minority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-NY)WikiCommons/CC BY 2.0

(Requests for comments from numerous Republican Senators on the HIV-related impact of the president’s budget and the AHCA went unanswered.)

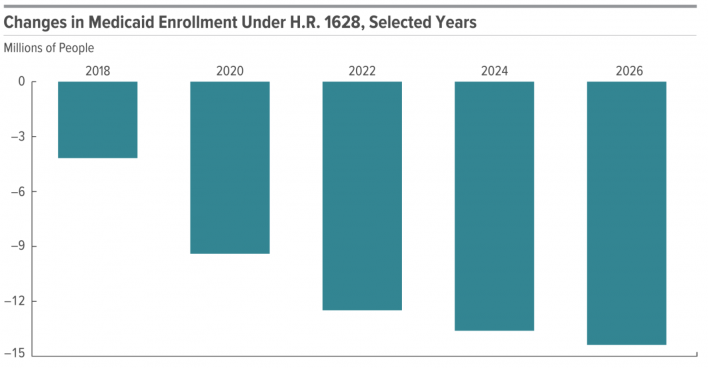

The May 24 release of the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report estimating the AHCA’s impact sent a bruising message that, compared with projections based on the current health care law, 14 million fewer Americans would have health insurance in 2018, a figure that would swell to 19 million by 2020 and 23 million by 2026. (These projections do not factor in the president’s proposed budget cuts that affect health care.) In 2026, the estimated number of uninsured people younger than 65 (and therefore largely ineligible for Medicare) would be 51 million, compared with a projected 28 million if Obamacare were left intact.

This loss of health insurance would disproportionately affect older people with lower incomes, in particular those between 50 and 64 years of age with incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), or $24,120 for individuals.

Given demographic trends, such a bias against late-middle-aged people with chronic health conditions would likely have a considerable impact on the aging U.S. HIV population, which tends to be lower income. While just one third of those living with the virus were 50 or older in 2010, that proportion is expected to rise to one half by 2020. Currently, only a sliver of U.S. residents with HIV are 65 or older and therefore have access to Medicare (neither the president’s budget nor the AHCA target that program). Even by 2030, only a fifth of the HIV population is expected to be in their senior years.

How the budget and the AHCA target Medicaid:

If enacted, the president’s budget and the AHCA would set in motion cuts to Medicaid so drastic that by 2027 federal spending on the program would be an estimated one half of what it is today, even without accounting for inflation. Over the next decade, the health care legislation would slash $834 billion from Medicaid while Trump’s budget proposes axing $627 billion in support for the program; the potential overlap between those two figures remains hazy.

Estimated declines in nationwide Medicaid enrollment (not specific to people with HIV) under the AHCA, also known as House Resolution 1628Congressional Budget Office

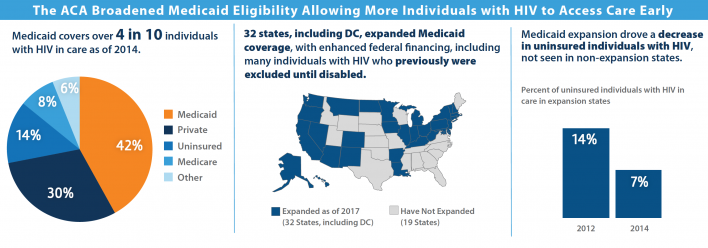

Medicaid is the primary source of insurance coverage for people with HIV in the United States. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, in 2014, 42 percent of U.S. residents in medical care for HIV were on Medicaid, a figure that rose from 36 percent in 2012 thanks to the expansion of Medicaid in states that opted to do so under the ACA. (Compared with the highly restrictive traditional state Medicaid programs, expanded state Medicaid programs have a simple cutoff for admission: having an income below 138 percent of FPL, or $16,643 for an individual.) By comparison, 30 percent of those in HIV care were privately insured in 2014, 14 percent were uninsured, 8 percent had Medicare, and 6 percent had some other form of health coverage.

The House health care plan would also forbid any new states from receiving federal matching for expanded Medicaid programs (32 states plus Washington, DC, have adopted expanded Medicaid since 2014). And starting in 2020, the federal government would cease providing matching funding to states for new enrollees to existing expanded Medicaid programs. Meanwhile, participation in such programs would likely ultimately wither under attrition because federal matching would end for any enrollee who experienced a gap in expanded Medicaid coverage of a month or more.

In states that expanded Medicaid, steadily doing away with the program would reintroduce a health care catch-22 of the pre-ACA era, in which someone with HIV typically had to have AIDS (and therefore a disability designation) before Medicaid could cover them and provide the antiretrovirals (ARVs) that would have spared them from a depleted immune system in the first place.

How the ACA’s Medicaid expansion broadened access to health coverage for people with HIV.Courtesy of Kaiser Family Foundation

And then there’s private insurance:

Starting in 2020, the AHCA would end the progressive income-based subsidies available for nongroup private insurance plans—non-employer-based insurance purchased on the open market. In their place would come an age-based system of federal subsidies—tax credits that would phase out for those with incomes between $75,000 and $115,000. The credits would increase from $2,000 annually for individuals up to age 29 to $4,000 annually for those age 60 and older. Levels of premium assistance would also no longer vary regionally according to differences in plan costs across the country.

Beginning in 2018, insurers would be permitted to charge premiums five times greater for older individuals compared with younger ones, stretching the current permitted ratio of three to one.

A surcharge up to 30 percent more in premium costs for the first year of a nongroup health plan would hit those applying for coverage who experienced a 63-day-plus gap in health coverage during the previous year. According to Andrea Weddle, executive director of the HIV Medicine Association, this bump in cost “is likely to make health care coverage unaffordable for many people with HIV who have a gap in coverage.”

States could otherwise apply for a waiver permitting insurers to adjust the cost of health plan premiums based on an individual’s health status and his or her expected health care costs—a process known as medical underwriting—for those who fail to prove they had continuous health coverage for the previous 12 months.

“The AHCA provision that punishes people with chronic diseases for lapses in their coverage, something people living with HIV often have no control of, is immoral and inhumane,” says Representative Barbara Lee, a California Democrat and longtime friend to the HIV cause.

U.S. Representative Barbara Lee (D-Calif.)

According to Weddle, people with a preexisting condition like HIV, “whose employment status or ability to maintain coverage may fluctuate due to their condition,” would be among those “most at risk for being subject to the premium penalty or being charged higher premiums based on their health status.”

A second optional waiver would allow states to rewrite the roster of essential health benefits (EHBs) that Obamacare has dictated private insurers must provide to consumers. These include coverage for prescription drugs, hospital inpatient care, chronic disease management, preventive services such as HIV testing, and mental health and substance abuse treatment. According to a recent National Association of State & Territorial AIDS Directors (NASTAD) brief, plans in states that axed key EHBs could leave people with HIV “with health insurance that does very little to provide meaningful access to care and treatment.”

The CBO estimates that states covering one sixth of the U.S. population would opt for both the medical underwriting and EHB waivers. Consumers in these states would likely be able to choose between medically underwritten plans or community-rated plans, with prices geared to their geographic area and smoking status.

In these states, the CBO predicts, the cost of community-rated plans would rise such that people with preexisting conditions who have had a gap in insurance coverage “would ultimately be unable to purchase comprehensive nongroup health insurance at premiums comparable to those under current law, if they could purchase it at all.”

For those with high health care costs who do maintain coverage with a private plan, out-of-pocket costs would likely increase the most in these states compared with those that sought fewer changes to state health care regulations.

States accounting for about half the U.S. population would apply for neither waiver, the CBO predicts. In those states, average premiums in 2026 would be an estimated 4 percent lower than they would be with current law. However, because starting in 2019 insurers could charge more for older people, those approaching age 65 would face steeper costs.

The remaining one third of the population would live in states that the CBO projects would make moderate changes to health care market regulations. Thanks to policies offering fewer benefits, premiums would be about 10 to 30 percent lower in 2026, depending on the area of the country, than they would be under current law. Younger people would reap greater savings.

The CBO report breaks down projections of what 21-, 40- and 64-year-old individuals would pay in annual insurance premiums for nongroup plans in 2026 if the current law persisted or if under the AHCA these individuals lived in a state that either did not seek waivers for market regulations or sought moderate changes.

For an individual with no spouse or dependents making 450 percent of FPL ($68,200), average premiums under the AHCA would wind up substantially cheaper in 2026 than with Obamacare for 21-and 40-year-olds while costs would remain in the same ballpark for the 64-year-olds regardless of the health care legislation in place.

As for those with an income at 175 percent of FPL ($26,500), average annual premiums in 2026 would be $1,700 with Obamacare still in place, regardless of their age. Under the AHCA, in the states seeking no waivers or moderate health care regulation changes, 21-year-olds would see respective annual premiums of $1,750 and $1,250; 40-year-olds would experience slight relative rises of a respective $2,900 and $2,100; and the 64-year-old’s costs would skyrocket compared with those under the ACA to a respective $16,100 and $13,600—amounting to more than half their income.

The report also stresses that reductions in EHB protections could substantially raise out-of-pocket costs, particularly for mental health and substance abuse care, both of which are integral to the wraparound services that many people living with and at risk for HIV need for optimum health. Additionally, benefits no longer deemed essential by a state might wind up subject to annual or lifetime benefit caps—a policy shift that could hit people who take expensive prescription drugs such as ARVs.

The AHCA would establish a fund of $123 billion (spread over nine years) for so-called high-risk pools to subsidize coverage for people shut out of the insurance market because of preexisting conditions. But such a source of health care coverage has a notorious history of inadequacies, including high costs to the consumer. Furthermore, experts consider the AHCA’s funding for high-risk pools a relative pittance in the face of a probable heavy need for such alternatives.

Last, even if any health care legislation is doomed to die in the Senate, the overall morass engulfing the future of U.S. health care policy “has the effect of potentially destabilizing the market,” according to Jennifer Kates, PhD, the director of global health and HIV policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation. With insurers currently in the process of setting the prices for 2018 Obamacare nongroup private plans, Trump’s refusal to indicate whether he will exercise his executive authority to cut off federal subsidies for private insurance premiums, may ultimately drive up next year’s premiums.

A Safety net: the Ryan White CARE Act

On the bright side, the Ryan White CARE Act, a federally funded program established in 1990 that has long benefited from bipartisan backing, would remain a vital safety net providing financial support for the care and treatment of people with HIV who lack insurance or are underinsured.

Fortunately, Trump has spared the divisions of Ryan White that provide care and treatment benefits from significant proposed cuts. However, according to Wendy Armstrong, MD, the chair of the HIV Medicine Association, “Ryan White has been essentially flat funded, or not keeping up with inflation, for many years.” The program, she says, is “stretched significantly, and a greater patient influx into that system will stretch the program even more.”

It wasn’t so long ago that people with HIV died while wait-listed for drug coverage from Ryan White’s AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP)—at its peak, the cumulative list stretched to 9,000 people—because they lived states with slimmer matching budgets to the program.

The president’s 2018 budget would, however, eliminate two Ryan White programs entirely: the AIDS Education and Training Centers (AETC), which receives $34 million annually to provide vital training for physicians in caring for people with HIV; and the Special Projects of National Significance (SPNS), which develops innovative models of care for the HIV population with an annual budget of $25 million.

Additional cuts and effects:

Driving down insurance rolls could also greatly compromise efforts to prevent HIV transmission. Recent innovative local efforts to reduce new-infection rates in places such as San Francisco and New York City lean upon the Obamacare-finessed ease of insurance access. This benefit helps ensure that an increasing proportion of those living with the virus gets on ARVs and develops an undetectable viral load, thus likely all but eliminating their risk of transmitting the virus to others. Additionally, the ACA likely fuels access to PrEP for those at risk of HIV.

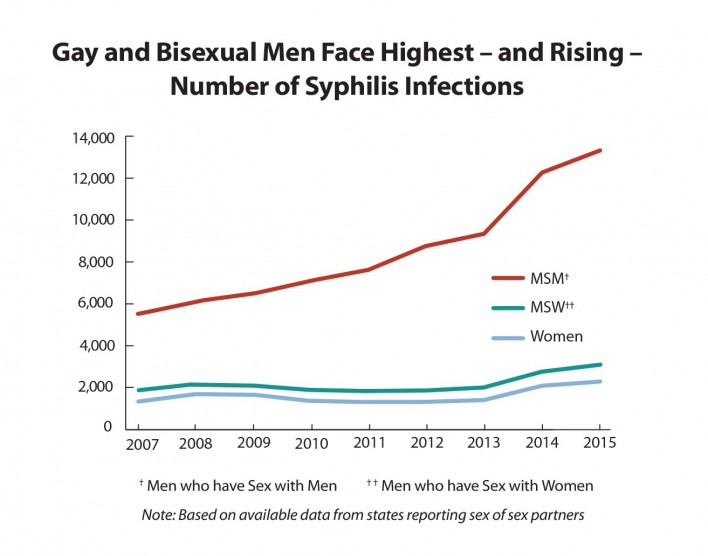

Additional proposed HIV-related cuts in Trump’s 2018 fiscal year proposal include: eliminating the entire $54 million budget for the Secretary of Health and Human Services Minority AIDS Initiative (MAI) Fund; a 15 percent, $17 million cut from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s MAI budget; axing 7 percent of the budget, or $26 million, for the Housing Opportunities for People with AIDS (HOPWA) program at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development; a 14 percent, $22.3 million cut to sexually transmitted infection prevention efforts at the CDC just as STI rates are rising; and a one-year elimination of federal funds to Planned Parenthood, which is a major source of HIV testing and prevention services nationwide.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/2015 STD Surveillance Report

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) would incur a $7.2 billion annual cut, seeing its budget drop by 22 percent. This includes an 18 percent, $550 million cut to HIV research efforts. Such an elimination of funds would likely have a considerable impact on the global epidemic, possibly resulting in scaled-back research into numerous important avenues, including the quest for HIV vaccines and cure methods.

Calling the president’s budget “heinous,” Representative Barbara Lee says its passage “would abdicate U.S. leadership in the fight to cure HIV/AIDS on the global stage and gut efforts to combat HIV in the world’s poorest countries.”

Indeed, with the United States by far the greatest funder of international HIV-related aid, Trump has proposed slashing the nation’s annual $6 billion budget for such efforts by $1.1 billion, or about 20 percent. According to amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research, the $225 million cut to the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) alone would drive 250,000 people off HIV treatment and orphan 78,000 children.

Finally, the CDC would incur a $149 million cut to its annual HIV prevention budget, a 20 percent drop. Considering that CDC dollars are responsible for a majority of HIV prevention expenditures in the United States, such a hit would compromise the ability to control the epidemic just as recent so-called high-impact efforts on the part of the CDC were apparently starting to bear fruit, helping drive down rates of new HIV infections 18 percent in six years.

Trump’s 2018 budget proposalWhitehouse.gov

3 Comments

3 Comments